Batman, as I’m sure you’re aware, has himself some Daddy

issues. Seeing your parents gunned down as a child will do that to a man. A

Freudian would say that he’s frozen by trauma at the point where he still sees

his father as a god, so when he becomes a man and hence becomes his father, he

tries to become the same. We all know how that turns out.

The main way that Bruce’s loss of a father expresses itself,

aside from the whole Kevlar Dracula thing, is in the vast collection of

surrogate fathers he collects around himself. Bat-books have been rolling off

the presses for 75 years now, and in that time Bruce has

collected a truly staggering number of older gentlemen to raise him. From Zatara

to Wildcat to Henri Ducard, each has imparted some nugget of dubious wisdom to shape the frightened billionaire child into the clown punching ninja we know

today.

|

| Long Halloween, Jeff Loeb and Tim Sale |

I’m going to dig into three of the best-known of these fathers. These are all men who have

played an instrumental role in moulding the Caped Crusader, men he's turned to as replacements for the late lamented Thomas Wayne. Two of them have done a poor job, in completely opposite ways, and one of them is just the father that he needs.

Before we begin, let me just say – I understand that this is fiction. These aren't real people with internal worlds, and

anything that could be said about them can be immediately countered with “but

that’s necessary for the story to work” or “but that’s just comics.” Those things are certainly true, and I’ve employed them often enough myself, but let’s be

honest here – they’re not very fun. I want to take a scalpel to these

characters, and that means pretending that they’re real people whose actions

have motivations and consequences. I hope that you can come along with me.

Another thing – yes, this is all about fathers. It’s not

like Bruce didn’t have a mother, but unfortunately her role in most versions of

the story is to turn up and get shot. Her pearls are better known than she is.

There have been a few stories that attempt to flesh her out - Greg Rucka’s

excellent Batman: Death and the Maidens

and Andrew Vachss’s terrible Batman: The

Ultimate Evil leap to mind - and

you can even see the pre-nu52 Leslie Thompkins as a replacement maternal figure for

Bruce. In the end, it’s the male role model that writers have chosen to

focus on, so I’ll be following suit.

|

| Batman 686, Alex Ross |

First up - Alfred Pennyworth. Legal guardian and manservant to Bruce, faithful right hand to Batman. This former actor and British

intelligence agent comes to serve as the Wayne family’s butler after his own father passes, and adopts the paternal role after the death of Thomas and Martha. He's been there almost from the beginning, first appearing in 1943's Batman #16. though he was originally a rotund bumbler and comic relief before being revitalised by William Austin's slender, moustachioed portrayal in the Batman serial later that year. Today he serves as Batman's mission control, quartermaster and faithful right hand in his war on crime.

Alfred's role in shaping Batman cannot be underestimated. It was his strong hand that got Baby Batman through those first dark days, teaching him that there was still goodness in the world even after the most important people in his life were snatched away. Without him there would be no Batman, even if he might prefer to see young Master Bruce settle down with someone nice instead of going out in the rain every night to catch his death of cold.

|

| Batman RIP, Grant Morrison and Tony Daniel |

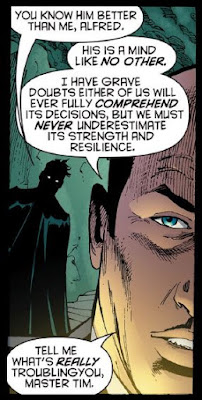

A stalwart ally, and a fine father figure, it’s true, but

consider: this is a man who allowed a traumatised child to grow into a man who

spends his evenings clenching his teeth on gargoyles and falling in love with literal cat burglars. There have been many versions of the Batman origin story, but when Bruce takes on the mantle of the Bat, Alfred is usually shown to briefly protest and then go along with things completely. He’s utterly indulgent of his ward, incapable of exhibiting

any sort of control or limitation, until his entire life becomes focused

around another man’s flying-mammal-themed monomania. His initial resistance to Bruce’s obsession dissolves into little more than the occasional cutting remark and reminders to eat and sleep. He’s completely without self, a trait which reaches its logical conclusion in Frank Miller's The Dark Knight Returns, which has him dropping dead the instant Bruce retires from crime fighting.

Alfred might have

Bruce’s best wishes at heart, but a father needs to set boundaries, and he is incapable of doing so. Despite his wealth of personal experience,

he accepts that Bruce knows better than him in virtually every circumstance,

putting his charge’s needs before his own regardless of the cost. Don’t

get me wrong – I’m not saying that Bruce should lose the cape and get to a

therapist’s office, though maybe sticking his head in now and then wouldn’t

help – I’m saying that it’s unhealthy for Alfred’s will to be completely

subsumed by Bruce’s.

What’s at the opposite end of the spectrum to Alfred? Who is

the father that demands everything and gives nothing? Well, that would be Shirtless

Duel Enthusiast and all around bad person Ra’s al Ghul.

|

| Batman #244: The Demon Lives Again, Denny O’Neil and Neal Adams |

First introduced by Denny O’Neil in 1971, the man known as

the Demon’s Head is an immortal Middle Eastern (despite every live action casting choice) warrior who leads the League of Assassins, an

organisation which has variously been a cult, an army and an ecological terrorist

groups. His motivations shift from writer to writer, but generally he pursues his own brand of brutal, uncompromising justice, with no qualms about killing

thousands in pursuit of the greater good. His brilliance and resources,

combined with the belief that his personal trauma gives him the right to reshape

the world, makes him a perfect foil to Batman. Ra’s has often expressed the desire to see Batman join him in his mission,

either as his right hand or even his successor.

|

| Son of the Demon, Greg Rucka and Jerry Bingham |

More than once, Ra’s has been placed in a position to guide Batman onto a darker path. His daughter Talia is one of the Caped Crusader’s most

persistent love interests, and the Demon has regularly expressed the desire to

see the two of them mated – it’s hard to live a few thousand years without

developing an interest in eugenics, after all. He demands everything from Bruce

and Talia, and sees them as nothing more than pawns for his eternal mission. This

gets literal more than once - in The

Return of Ra’s al Ghul he tries to take over the body of his grandson

Damian (gross) and in Batman Beyond he

pulls it off with his own daughter (GROSS!). In Son of the Demon Batman goes to live with Ra’s in his Bond Villain

Ice Fortress for some reason, and Christopher Nolan’s version even trains him in the way of

Frozen Lake Ninjutsu. On TV, Batman stand-in Oliver Queen submits himself to

Ra’s tutelage as well - I haven’t finished season 3 of Arrow, but I assume that he finds

an appropriately shirtless way back to the righteous path.

Batman always pulls himself back onto the side of the angels, but it's been a near thing more than once. There's something very seductive about what Ra's offers him - a chance to truly change the world, to alter whole economies and governments instead of stopping crime one mugger at a time. The price, however, is too high. Even an indomitable will like Batman's can't take take charge of the League of Assassins without becoming a killer - after all, it's right there in the name. Ra's might see him as a son, and certainly respects him more than he does anyone else, but he cares nothing for Bruce's moral code. He doesn't even delight in trying to make him violate it, in the way the the Joker so often does - it simply doesn't doesn't matter to him. Nothing matters to Ra's except for Ra's.

So we have two fathers – one who gives too little, and one

who gives too much. One who cares only for his own will, and one whose will has

been completely subsumed. There has to be a middle ground, doesn’t there?

Someone who can provide guidance while still allowing his charge to flourish,

someone who represents a structure that Batman can press against, but grow and

learn in the process?

That’s where this guy comes in.

|

| Battle for the Cowl: Commissioner Gordon, Royal McGraw and Tom Mandrake |

Police Commissioner James Gordon debuts all the

way back in 1939’s Detective Comics #27,

the very first Batman story. We actually see Gordon before we see the man

himself. Jim is Gotham’s most stalwart guardian, doing with a dirty trenchcoat

and a six shooter what Bruce does with a billion dollar budget and a

superpowered alien best friend. He’s a man with a strict moral code, one

that he’s flexible enough to bend when circumstances demand, and arguably the

man that Batman respects the most, excluding those who changed his diapers. In

most versions of the story, he’s the one that Batman goes to first when he

starts looking for allies, recognising that vigilante work on his scale is impossible without the help of the one good man in Gotham's corrupt police force.

Most importantly for our purposes, he’s a man of the law,

something that Batman definitively works outside of. Gordon is at first deeply

reluctant to work with this masked stranger, and Batman has to prove that he’s

on the side of the angels before the grumpy old cop will trust him. Different versions of the story show this unfolding very differently, with the Nolan version taking his side almost immediately, while Snyder's Zero Year gives Gordon a deeply antagonistic relationship with both Bruce and Bats before he slowly comes around. In the

process, Gordon’s moral code becomes Batman’s, or at least serves as one of its guiding lights.

|

Batman #0, Scott Snyder

and James Tynion III

|

Gordon calls out Batman when he needs to be called out,

talking straight to the scariest man in the city. Bats might not always

listen,

at least not at first, but in the end he comes around. He needs the

structure

that Gordon provides, much as he might sometimes rage against it, or see

himself as being above it. Much like a child, he might want to be able

to do whatever he wants, but it's when placed within a set of rules that

he respects and understands that he flourishes. The Gotham legal

system, as broken and corrupt as it might be, is that structure. Batman

isn't judge and jury, and he certainly isn't the executioner - that's

why captured criminals wind up trussed up on the steps of the police

station, rather than being directly punished by Bats himself. (usually - we can talk about Ten Nights of the Beast another time) In both a

direct, character sense, and a broader narrative sense, Gordon

represents this truth.

|

| Batman: No Man’s Land volume 4, Greg Rucka and Rich Burchett |

Gordon provides Batman with legitimacy. Because he accepts

Batman, working with him as closely as he can, Batman is able to operate in his

city relatively unmolested. Without that support, his mission would be

near-impossible, something we see in stories like Zero Year, Year One or the animated series episode Over The Edge. Batman ignores Alfred’s

wishes and fights against Ra’s al Ghul’s, but Gordon’s are paramount to the success

of his mission. He is the father that Bruce cannot ignore, and his is the trust that he cannot do without..

How much does Gordon trust Batman, you might ask? How certain is he that this masked rubber fetishist isn’t going to turn on a dime and start collecting heads? Completely. After all, he trusts him with the most precious thing in his world - his daughter. Gordon’s eldest child, Barbara Gordon, aids Batman in his war on crime, first as Batgirl and then as Oracle and eventually as Batgirl once more. She’s the high flying computer genius that Batman needs, and though the idea doubtless terrifies him, Gordon lets her choose her own path.

|

| The Dark Knight Returns, Frank Miller |

How much does Gordon trust Batman, you might ask? How certain is he that this masked rubber fetishist isn’t going to turn on a dime and start collecting heads? Completely. After all, he trusts him with the most precious thing in his world - his daughter. Gordon’s eldest child, Barbara Gordon, aids Batman in his war on crime, first as Batgirl and then as Oracle and eventually as Batgirl once more. She’s the high flying computer genius that Batman needs, and though the idea doubtless terrifies him, Gordon lets her choose her own path.

Okay, technically, Gordon doesn’t know. But let’s be real:

he’s the second greatest detective in the city. He’s extremely close to his

little girl. He see’s Batgirl all the time. He

knows. Like the best sort of father, he does what he can to keep her safe,

but he lets her make her own choices. Just as he does with Batman - he might wish deep down that he'd take off the mask and pick up a badge, but he understands that his strange, growly-voiced son is doing things his own way, and he's learned to respect that.

|

The New Batman Adventures, Over the Edge (episode 12)

|

The trust between Gordon and Batman is strong, but it isn’t

unconditional, and that’s important. Gordon understands that Gotham needs

Batman, and he works as closely with him as he can, but that’s contingent on

Batman’s hands remaining clean, or at least clean-ish. Batman goes where the law can't, and uses morally grey tactics that Gordon wouldn't, but he doesn't kill. This is for his own moral reasons, of course, but it serves a functional purpose as well. Bruce knows that if he were to ever cross that

final line, he would lose his greatest ally on the spot.

The more you think about it, the clearer it becomes that Gordon is the key to understanding Batman. Alfred and Ra's represent two possible failings for Batman - a collapse into complete self indulgence on the one hand, or an abandonment of everything that sets him above his enemies on the other. Gordon is the father figure that keeps him on the straight and narrow, letting him be himself, but not so much that he forgets the needs of others. Gordon’s guidance is healthy, and Gordon's fatherhood is the most necessary, quite simply because it leads Batman to be his best

and truest self.